Mitchell

Machine Works is in the business of building complex machines. Hailing from

Dalton, Ga., the company has been known the world over for its Magic Carpet, a

hydraulically driven roller system that can roll up, or roll out, an entire

sports field of turf in a matter of minutes.

Mitchell

Machine Works was founded in 1967 by the company’s self-described “chief

engineer, owner and just about everything else,” Mark Mitchell, who has gained

a reputation for being someone who can design and deliver complex machines.

Because of this pedigree and his previous experience building the Magic Carpet,

Mitchell picked up the phone one day and found himself with some surprise

business. On the other end of the line was a company that needed Mitchell to

build an indoor running track.

Taken

at face value, building an indoor running track doesn’t seem all that

mechanically complex. A track’s essentially an oval. A flat oval.

But

there was a catch.

Instead

of being flat, the indoor running track that Mitchell was being asked to build

had to be hydraulically driven, because, you see, some indoor track events use

a banked surface, not a flat one like its outdoor counterpart.

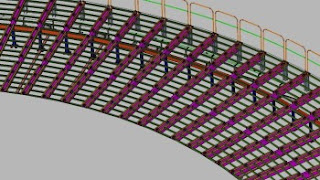

As

you can imagine, building a banking hydraulic indoor running track isn’t a

straightforward endeavor. In fact, building such a machine requires some

200,000 pounds of steel and 72,000 components (including 72 hydraulic

actuators)—and that doesn’t even take into account the 7,000 work hours

required to build the machine. What’s more, for an indoor track to work

properly, it has to work in perfect harmony, with each of the hydraulic drivers

that lift the track’s banks working in unison with its nearby neighbors.

As

Mitchell described it, one of the biggest issues facing the design of this

track was figuring out the complex control system that would be used to govern

how each hydraulic actuator worked, because as Mitchell noted, “given the

torsion in the system, no cylinder could be more than 10 mm out of line with

its neighbor.” To transform this seemingly intractable problem into something

more manageable, Mitchell looked to IronCAD.

Mitchell's Hydraulic

Track in IronCAD

Although

Mitchell is familiar with CAD, he turned much of the actual CAD work over to RJ

Saucier of Genesis Technology Systems. Working in concert with Saucier,

Mitchell was able to create a robust CAD model using IronCAD that gave him

great insight into how the hydraulic system worked.

Once

Mitchell’s vision for his indoor track had been modeled, Saucier and his team

set out to analyze how the track’s movement would affect its overall

performance. Using IronCAD’s finite element analysis (FEA) tools, each

component in the assembly was tested, and when errors that would affect the

performance of the track were found, the design was slightly modified.

“One

of the best parts about IronCAD is the fact assemblies are so easy to use,”

said Saucier. “You’re never hung up with constraint sets, so when a client

comes in and needs a quick change, say, this component needs to be moved over

one-sixteenth of an inch, IronCAD can do that quickly without having to

untangle an assembly connected mess.”

With

this analysis at hand, Mitchell and Saucier were able to articulate their

assembly and move the track as it would move in reality. Because of the

integrity of the geometry in their model, Mitchell could accurately measure how

much each hydraulic cylinder would move at different points along its path as

it was raised and lowered. With those numbers in hand, Mitchell was able to

give the programmers developing his control system detailed instructions

describing the positions of each hydraulic cylinder as it moved through the

banking operation.

“Trying

to make 36 cylinders dance together is tough, but with IronCAD we were able to

simplify the design control system design process,” noted Mitchell.

CAD as an

Installation Tool

Beyond the fact that IronCAD was instrumental in designing

Mitchell’s track, it also played a role in making the assembly of his track

much easier. Not only was Mitchell able to use detailed drawings to transform

those 72,000 parts into one working whole, he also used IronCAD’s software to

give instruction to the workers assembling the track. Whenever communication

problems would arise during the assembly process, Mitchell was able to bring up

a detailed 3D model directly in IronCAD and specify exactly

how a subsystem should be assembled and why.

Given that level of communication, Mitchell was able to cut down

his time on site and have his track built efficiently.

With one completed track behind him and a second nearing completion, Mark

Mitchell is confident that his hydraulically articulated indoor track’s design

represents the shape of things to come in multipurpose sports facilities being

built around the world. Still, Mitchell realizes that each and every track

design will be different, requiring minor tweaks and work-arounds that will

alter his original design. Fortunately, Mitchell is confident that he can meet

any design requirement thanks to the robust design and analysis tools that he

has in IronCAD today.

IronCAD has sponsored this post. It had no editorial input. All

opinions are mine. —Kyle Maxey

No comments:

Post a Comment